“Why is it considered a burden for parents to select what’s best for their children to learn? That’s the parents’ duty. My job is to help the parents provide that teaching.”

~Mahrree Peto, The Forest at the Edge of the World

I drafted those words—the question of a school teacher in a different time and in another world—over four years ago, before I knew anything about Common Core Curriculum. As a homeschooling mom since 2002, and a college composition instructor, I’d developed my own concerns about public education long before I was forced to confront Common Core head on. But the worries I had then about schooling have now festered into an ulcerous wound.

Education used to care about the children; now the system serves only itself.

I remember reading about Laura Ingalls Wilder, and how the parents were the school board, the parents chose the teachers, and the parents decided how they wanted their children educated.

I don’t need to tell any of you how far we’ve run away from that idea.

Not so long ago most children in elementary enjoyed school, their natural curiosity still remaining intact despite the introduction of bubble-sheet testing which I remember with lingering trauma in the 1970s. While it certainly wasn’t perfect, school was more about doing the times tables, spelling tests, listening to the teacher read from a novel out loud for an hour after lunch (yes, really), enjoying three (yes—three) recesses, spending time in music, and doing weekly art projects that frequently took quite a bit of time but resulted in rather amazing things. And this manner of education—again, while not perfect—still produced from my school many doctors, professors, scientists, and humanitarians.

For those of you don’t know, that’s now how school is anymore.

When I first pulled my children out in 2002, my then-first-grader’s teacher told me, “I’m so glad to see you doing this. When I first started teaching thirty years ago, my purpose was to show children the joy in learning about the world. Now we can’t do that. We teach coding, we teach filling in bubbles—heaven forbid I should try to make anything, especially reading, fun.”

Now, it’s not the idea of a universal core of knowledge that’s disappointing, but the application of it. In frenetic attempts to follow the Common Core Curriculum standards sold to schools—along with the bribe of funding—teachers have been forced to impose lessons and practices that leave the parents scratching their heads. My kindergartner last year spent a great deal of time filling out answers on bubble sheets, a not-so-subtle intimation that her ability to properly color in the little circles will be crucial to evaluating her future.

No, I don’t know who this is, but I concur with the sentiment.

Her first grade is proving to be more of the same, and now with timed reading tests designed to push six-year-olds to read random words faster and faster. Comprehension doesn’t seem to be a concern; only speed. My daughter is slowly beginning to lose heart.

At back-to-school night last month I heard many mothers express how, in kindergarten, their children were so excited for school, but now some of their fifth graders dread each day.

“What happened?” I heard one genuinely confused young mother say to her friend. “And does it get worse when she hits middle school?”

I was cringing so hard I’m surprised she didn’t hear it.

What happened?

We’re killing our children’s natural curiosity.

Will it get worse?

Uh, yes. Sorry.

How did this happen?

Through the same old nonsense we’ve always been dealing with in public education: the out-dated notion that all children are inherently the same, and can be “programmed” in the same ways to create the same output, namely an adult that will become an industrious worker.

The model doesn’t work; in fact, it has never worked for more than a fraction of the population. For as many doctors and professors my schools churned out, there were just as many who dropped out of college, failed to complete any kind of professional training, and never rose above being a checker at the grocery store. There are always children that fall through the cracks because they can’t fit the inflexible mold.

And Common Core, which is merely the same model in an updated website with a heavier hand and a stiffer mold, won’t succeed either.

First, anyone who’s had more than one child will tell you they are NOT all the same. I have nine, and you’d think that with so many kids we’d start recycling some DNA combinations. But mystifying each child is different, despite coming from the same gene pool, being raised in the same house, and eating the same food.

Half of my kids figured out reading at age 4. The other half couldn’t grasp it until age 9. One third of my children love math—one doesn’t even write down the formulas when he does algebra—while another third of my children tremble in terror when approached by a number attached to a letter. The other third are blissfully in the middle. Some of my kids find science dull, but others try to actively blow up the house while others try to put everything back together again. Some read nonstop all day long. Others grumble at the sight of the book.

Every child is unique, but years ago educators decided to shove them all into an assembly line of education where the same information is fed to them in the same way, NOT because it was the best way to teach, but because it was the cheapest way to process the greatest amount of students per teacher.

With all respect to John Locke, the tabula rasa notion of seeing humans as “blank slates” waiting for their minds to be filled with knowledge—a theory which has been debunked for generations, except among some educators with influence—ignores the fact that humans are born with personalities, with various learning styles, even with unique ways of perceiving the world. Ask any parent with more than one child: they come different.

Yet altering education to truly teach individuals, instead of groups, requires vast changes that education boards, university education departments, and most of all the government does not want to do, even though we see effective models in Europe and Asia. (And perhaps that’s why we don’t want to change; we resent the idea that someone else innovated something first.)

It’s simply too hard to change, argue those entrenched in the old traditions. Simply too hard to do the right thing.

So instead we take the outdated assembly line, add bells and whistles and unproven theories, and shove more kids through it hoping to disprove Einstein’s platitude that doing the same thing over and over, and expecting different results, is the definition of insanity.

Well, public education has gone insane.

And now, forcing Common Core—a method of teaching and an application of curriculum which has NOT even been fully tested—has dealt yet another great blow to children.

It’s making them hate school.

Now, I acknowledge that in every class there are those who will thrive. My 1st grader is like that: she loves school. However, already the love is fading. As I mentioned before, she’s growing discouraged. Despite reading at a 2nd grade level, she’s perplexed by reading rows of nonsense words and random sentences as quickly as possible in a minute, and math, which comes to her naturally, is becoming unnecessarily confusing. This frustration with education rarely occurred when we homeschooled.

I’m in a unique situation to compare the differences because I exclusively homeschooled my kids for nearly a decade, then put them into public school over two years ago when a pregnancy at age 42 scared me into thinking I wouldn’t be able to keep up with my kids’ needs. I had a 6th grader and a 7th grader thrust into the middle school, and they had never spent a day of school in their lives. We were all terrified. They adjusted and, to my great relief, they were not only on track but a little bit ahead, manifested by their straight A’s.

I also, with great trepidation, put my then 7-year-old high functioning autistic son into 2nd grade, and braced for impact. He had a very sweet teacher, concerned resource instructors, and eventually learned to read and deal with the crowd.

Still, he begged to come home for third grade, as did his older brother in 6th grade who found the math class too slow and the science too shallow.

Fast forward to this year; my now 9-year-old autistic son wanted to try 4th grade, hearing about how great the teachers were, and wanting to spend more time making friends. So we eagerly prepared him making sure his was on target academically and as socially as an autistic boy can be. He was ready!

It took only one week for him to beg to come back home.

At three weeks, he started clenching his fists when trying to complete math pages that were filled with several methods of doing multiplication our trusty Saxon math didn’t cover. And then, faced with the option to complete a problem such as 49 x 28 = ? in any of the three ways he’d learned, he’d freeze, unable to know how to proceed. (For examples of the multiplication confusion some of our children are exposed to, watch this video.)

At four weeks he started clutching the sides of his head every night as he looked at his homework and whimpered, “I’m too stupid!”

That’s when I started getting mad.

He’s not stupid. Want to know about pyroclastic flows? Tectonic plates? The theories behind black holes? Ask him, but then make yourself comfortable because you’re going to hear everything. He’s read all he can on the subjects and knows the documentary section of Netflix as intimately as some kids know the starting lineup of a basketball team. Ask him about ecology, and get ready to hear a dissertation about saving the environment, misconceptions about global warming, and his opinion on the big bang theory. Remember, this kid just turned 10-years-old.

But because he can’t conform to the Common Core Curriculum he thinks he’s stupid and he hates school.

At his parent-teacher conference I learned that academically, he’s right on track.

But at his nightly parent-child conferences, I’ve learned that his anxiety is through the roof.

So Friday was his last day of school. We’ve quit Common Core, and starting Monday he’s schooling at home.

His frustration is not just because he’s autistic, either. I have a junior in high school taking math who asks me every night for assistance. Not even his teachers can fully understand the homework, tell their students to skip certain problems, and the photocopied pages they use have so many errors it likely doesn’t even matter what the real answers are.

My 9th grader is also expressing similar frustrations, and asked to be homeschooled part-time this year because Common Core was so focused on filling in the right bubbles for the tests that she anxiously felt she wasn’t learning anything useful.

Anxiety and stress do not improve education; they strangle it. Learning can be a joy, but oddly our society has adopted the notion that if there isn’t suffering, there isn’t progress.

If you think junior high kids are moody now, just watch what will happen to our elementary kids over the next few years. I fear that by the time they become teenagers, their teachers will be permanently on valium.

There are many other arguments about the insufficiencies of Common Core, about how it was foisted upon states by dangling the lure of money in front of them, and how its main purpose is to produce good workers, when, for years, many of us thought education was about producing a populace that could think for themselves and identify was is truth and what is error.

But what’s really baffled me for many years is why the government has decided parents are inadequate in knowing what’s best for their children. I started writing my books in an effort to puzzle it out.

“Miss Peto, why do you find it disturbing that the Administrators select what’s most important for our children to learn?”

She really wasn’t sure, but it sat on her strangely. “Captain, what if the Administrators choose to teach that which is against the beliefs of the parents?”

“I can’t imagine any situation where the Administrators would recommend teaching anything that would be contrary to the welfare of the world,” the captain said. “If anyone would be out of line, it would be misguided parents.”

Exactly who would be deciding what was best for the world, Mahrree wondered, and what was best for an individual? (The Forest at the Edge of the World)

Why have we removed the curriculum decisions from the parents?

Could it be because our government has ceased to see us as someone they serve, and instead see us as a means to their own ends? My school teacher protagonist thinks so.

“You said the other day that I needed to get to the bottom of this!” she said fiercely. “Well, here it is: Parents are stupid, Administrators are smart. Hand over your children to the Administrators with no questions debated so they can pour their own ideas into the children’s minds, while parents worry about nothing else except getting more gold! Gold which they then hand over to the Administrators in higher taxes. Ooh, very clever! The Administrators get richer while families fall apart!”

Perrin’s mouth opened and shut several times, but he knew that when his wife was on a rant, there was no safe way to interrupt her.

“And then what happens to the children?” she gestured wildly. “Give the government a few years, and I’m sure they’ll be telling the children what jobs they can have, so they make sure our children make them enough gold and silver!”

Perrin lifted a finger, likely to try to interject that she had an intriguing point, but he pulled it back a moment later when she began to froth. His contribution could wait.

“Well, I’ve had enough. I’m going to give them a piece of my mind so they can see how intelligent mine really is!” (Soldier at the Door)

Yes, the nature of this character is to get a bit overwrought, but for what other purpose is there for the government to feel the need to take over the education of our children?

“Parents feel stupid because their government tells them they are, so they’re humbly—and even willingly—allowing someone else to guide their children’s teaching. But there’s another reason,” her husband hesitated. “This way the Administrators get to pick and choose what the growing generation learns, and anything that’s not supporting the Administrators simply isn’t covered. In one generation, the entire population should be as loyal to the Administrators as they are—or were—to their parents’ beliefs. Whatever they say, the people will believe.

“And that’s precisely what the Administrators want: the only authority influencing the world will be theirs.” (Soldier at the Door)

I submit that the federal government, in mandating what we teach our children, is attempting to influence the development of the rising generation so as to meet the financial and political needs of the government, not the needs of our children to become intelligent, thoughtful adults. No, this isn’t about mind control, but it’s a form of manipulation, of getting what they want out of us because they have all the power, and we have less every year.

Don’t believe the government is manipulative? As I write this the federal government has imposed a shut-down (or convenient slimdown, as some would argue) because of a budget impasse.

But the nature of the shut-down, and those areas that have been affected, is very subjective: subject to causing the most ire and discomfort among citizens. The randomness of road and park closures (outdoor monuments on the Mall in DC are suddenly inaccessible?), websites that are down (only because someone pushed a button to deny access), and services that are suspended (WIC’s been closed! Starving babies!) have all been carefully orchestrated to twang the most heartstrings with the least amount of effort.

Manipulation of the public, at its finest.

Just out of curiosity, I looked up “Ways to tell if you’re in an abusive relationship.” Read this list from Dr. Phil, and think of it in terms of the federal government and you. My friends, we ARE trapped in an unhealthy relationship.

I support my local school and the teachers—many of my friends are teachers—but I realize they have no power to stop this level of manipulation of public education. They, too, are stuck in an abusive relationship and are doing the best they miserably can in a bad situation.

But I’m fortunate in that I work only part-time, so I can, starting next week, teach my son at home again. He’ll learn tried and true math principles thanks to Saxon 54, he’ll learn to spell, and spell again, and spell yet again until he gets all his words right without the pressure of a ticking clock (which, autistics will tell you, can be quite maddening) and he’ll explore science and history without the fear that he’s hopelessly stupid.

I’m also not going to time how long it takes him to read something, because the boy doesn’t read; he savors. He analyzes diagrams and concentrates on charts. Pondering has become a lost skill, one that I refuse to deny my son. The point isn’t the volume of pages being read, it’s the depth of understanding he gets from the reading. As an English teacher, I’ve encountered many students who have read quickly through the texts, but remembered very little, so they have to reread, and reread yet again. Skimming isn’t the same as absorbing, but don’t tell Common Core that.

So today we quit Common Core, abandoned this one-sided relationship that doesn’t care one bit about my son but yet is obsessed with the data he produces.

But what about everyone else who can’t commit such a quiet act of pseudo-civil disobedience such as homeschooling in protest of Common Core? I wished we could band together and overthrow this nonsense, but that’s a bit vague.

What we can do is talk with our kids and let them know what we feel and think, how we believe and understand, and let them know that what they learn out there may not necessarily be what they should believe in here.

“There’s one thing we can do,” Perrin said. “We can make sure we’re not touched by whatever may be coming. In our house we will discuss and believe whatever we want. We can recognize for ourselves that the sky is dark and threatening with a storm obviously on the way, and explain to our children that the rest of the world has been conditioned to believe the sky is blue, despite all evidence to the contrary.” (Soldier at the Door)

My friend, a single mother who works full time and has two kids, wrote this: “I’ve come to the conclusion that school is where my kids go to be babysat while I’m at work, and they actually start learning when they get home. I have noticed that school seems to teach them WHAT to think, but not really HOW to think. I have to say that worries me the most. I try really hard not to browbeat my kids into agreeing with me, but I do want them to be able to back up their arguments logically.

“If I think of the schools as being responsible for educating the kids, I get very stressed out at the things they don’t know, and then get to stress again over the crap they ARE being taught. Some of the crap they come home spouting is just plain nuts, and it’s hard to stay calm sometimes during our little ‘debunking’ sessions. Makes for a really busy day for me, but sadly that’s how it is I guess.”

Yes, sadly for now, that’s how it is. But at least we still have the freedom to talk to and educate our children whenever and however is possible for us. And we better exercise that freedom for as long as we still can.

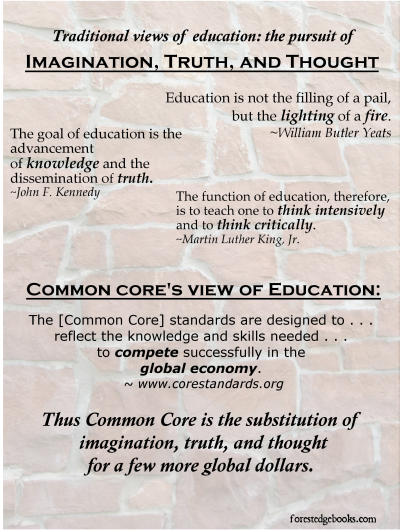

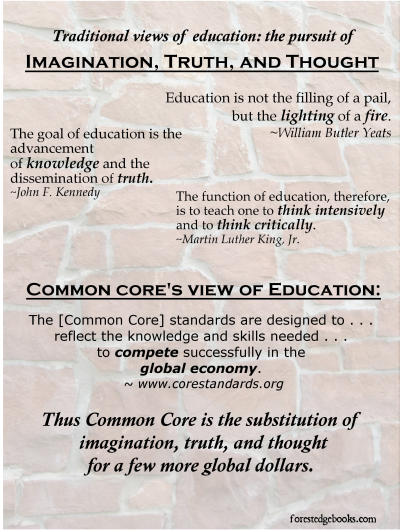

In the meantime, if you’re still unconvinced that the direction Common Core is taking us is not our children’s best interests, consider the changing opinion of the purpose of education. We used to be concerned about lighting the imagination, pursuing the truth, and developing critical thought, but no longer. Take a look at this statement from the Common Core website (emphasis mine):

The standards are designed to be robust and relevant to the real world, reflecting the knowledge and skills that our young people need for success in college and careers. With American students fully prepared for the future, our communities will be best positioned to compete successfully in the global economy. http://www.corestandards.org/

In other words, the purpose of education is to make money in the world. Common Core is demoting our children from thinking, creative beings, into busy little worker bees that make more honey for the governmental hive.

So if you think the purpose of life is to capitalize on the global economy, then surprise—Common Core is the route for you.

But I personally believe humans are destined for higher purposes and greater things. I’ve already discovered there’s much more to life than just money, and that’s what I want my children to discover as well.